howitreat.in

A user-friendly, frequently updated reference guide that aligns with international guidelines and protocols.

Venous Thrombo-Embolism

Introduction:

- Thrombosis is inappropriate formation of clot within the venous or arterial circulation.

Epidemiology:

- Incidence-

- Deep vein thrombosis (DVT)- 100 per 1,00,000 persons per year

- Pulmonary embolism (PE)- 117 per 1,00,000 persons per year

- 40-50% of patients with symptomatic DVT have silent PE

- 1-8% of patients with PE die because of complications

- Estimated death due to PE is more than combined deaths caused by carcinoma breast, HIV and motor vehicle accidents.

- Most of PE related deaths occurs suddenly, hence prevention is the most critical intervention.

Etiology:

Virchow’s triad:

- Hypercoagulability

- Stasis

- Endothelial damage

Hypercoagulability/ Thrombophilia

- Inherited thrombophilia states:

- Genetically determined increased likelihood of thrombosis

- Discussed separately

- Acquired Prothrombotic States

- Increasing age

- Pregnancy and post-partum status

- OC Pills

- Nephrotic syndrome

- Obesity

- Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome- Discussed separately

- Malignancy

- Paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria

Stasis

- Immobility e.g. long-haul travel, post-surgery/ trauma

- Venous stasis: CCF, Obstruction by tumour, varicose veins

- Increased blood viscosity: Polycythaemia vera and other myeloproliferative disorders, dehydration,

Endothelial damage:

- In-dwelling venous devices

- Chemotherapy

- Inflammatory states

- Intravenous drug abuse

- Malignancy: Cytokine release from tumours/ Local tumour infiltration

Classification:

- Calf/distal vein thrombosis- DVT confined to deep calf veins

- Proximal vein thrombosis- DVT involving popliteal, femoral or iliac veins

Clinical Features:

- Deep vein thrombosis:

- Acute onset of pain and swelling at a unilateral extremity associated with tenderness and erythema

- Sometimes palpable cord representing thrombosed vessel

- Phlegmasia cerulean dolens- Occlusion of whole venous circulation associated with extreme leg swelling and compromised arterial flow. It occurs due to massive iliofemoral thrombosis. Seen in <1% of all DVT.

- Post-thrombotic syndrome

- Pain, heaviness, swelling, cramps, itching/tingling of affected leg, skin induration and chronic dark pigmentation. In severe cases, there can be skin ulcers.

- These symptoms are aggravated by standing or walking.

- Seen in 25% patients with proximal DVT treated with anticoagulation.

- Results from venous hypertension which occurs due to valve damage. Defective valve function leads to increased pressure in deep calf veins during ambulation, which leads to blood flow from deep veins to superficial venous system. This causes edema and impaired viability of subcutaneous tissues.

- Sometimes this can result in venous ulcers.

- Pulmonary embolism: It has varying presentations-

- Asymptomatic

- Dyspnoea, pleuritic chest pain, cough, anxiety, hemoptysis

- Tachypnoea, tachycardia

- Severe dyspnoea due to right heart failure

- Cardiovascular collapse with hypotension, syncope and coma.

- 4% patients develop chronic thromboembolicpulmonary hypertension (Pulmonary artery pressure >25mm Hg) at 2 years of PE, due to chronic thrombo-embolism. Pulmonary endarterectomyalong with long term anticoagulation is the most effective treatment in them. Pharmacological agents such as bosentan (endothelial receptor antagonist) can be used in inoperable patients.

Investigations:

(Pre-test probability scores such as Wells score, modified Geneva scores and such several other algorithms were used earlier. Presently they are not being used)

Deep vein thrombosis

- Compression duplex colour doppler USG

- Test of choice in diagnosis of DVT

- Sensitivity and specificity- >97%

- Done using high-resolution real-time scanner

- Disadvantage- It cannot visualize iliac veins and segment of superficial femoral vein within the femoral canal.

- If it is normal and if there is strong suspicion of DVT (Positive D-Dimer), it should be repeated after 5-7 days.

- It remains abnormal for a year in 50% of patients. It can remain abnormal for even longer period in some patients.

- Phlebography/ venography-

- If USG is not available/ inconclusive/ repeat testing is impractical.

- It is reference standard for diagnosis of DVT, but is technically difficult.

Pulmonary embolism

- ECG

- Sinus tachycardia

- S wave in Lead I

- Q wave in lead III

- Inverted T wave in lead III

- New right axis deviation

- Spiral CT of lungs with pulmonary angiography

- Perfusion – ventilation lung scanning with 99m TC albumin macroaggregates. Normal scan rules out PE. But abnormal scan does not confirm PE.

- MRI

- Highly sensitive for PE

- Further studies are required to determine the clinical role.

Common to both

- Plasma D Dimer:

- Product of lysis of cross-linked fibrin

- Done by ELISA or latex agglutination method

- Simple, rapid, cost-effective first line exclusion test

- Positive test is non-diagnostic but negative test almost rules out VTE.

- It is positive several other conditions such as- infections, tumors, surgery, trauma, extensive burns, bruises, ischemic heart disease, stroke and pregnancy.

- Acute phase reactants

- Elevated levels of fibrinogen, factor 8, platelet count and total leucocyte count

Differential Diagnosis:

DVT

- Muscle strain/ tear

- Direct twisting injury to the leg

- Lymphangitis/ lymphatic obstruction

- Venous reflux

- Ruptured popliteal cyst

- Leg swelling in a paralysed leg

- Abnormalities of knee joint

- Sciatica

- Muscle hematoma

- Post-thrombotic syndrome

PE

- Atelectasis

- Pneumonia

- Pleuritis

- Pneumothorax

- Acute pulmonary edema

- Bronchitis

- Bronchiolitis

- Acute bronchial obstruction

- Myocardial infarction

- Cardiac tamponade

Pretreatment Work-up: (None of these are mandatory, choose those which are appropriate):

- History

- Examination

- Spleen:

- Hemoglobin

- TLC, DLC

- Platelet count

- PT

- APTT

- Peripheral smear

- LFT: Bili- T/D SGPT: SGOT:Albumin: Globulin:

- RFT: Creatinine: Urea:

- LDH

- UPT (If h/o amenorrhea)

- Anticardiolipin- IgG/IgM

- Anti β2 Glycoprotein I

- DRVVT

- JAK 2 Mutation

- CAL-R

- MPN

- Hb Electrophoresis (for HbS)

- PNH Workup by Flowcytometry

- CT – C/A/P +/- Tumor markers

- Urine routine(SOS 24hr urinary protein)

- Thrombophilia work-up

- In cases of Unprovoked VTE, VTE at unusual site, Recurrent VTE, VTE in <40yrs, VTE with strong family history, Unexplained recurrent pregnancy loss

- Do them 1 month after stopping Warfarin.

- If stopping not possible, do all tests except Protein C & S. Change to LMWH for 2 weeks, then test for Protein C and S and then restart Warfarin

- Tests included in thrombophilia workup

- Antithrombin Activity

- Protein C

- Protein S

- Factor V Leiden (PCR)

- Prothrombin G20210A Mutation (PCR)

- Factor VIII Activity

- S. Homocysteine

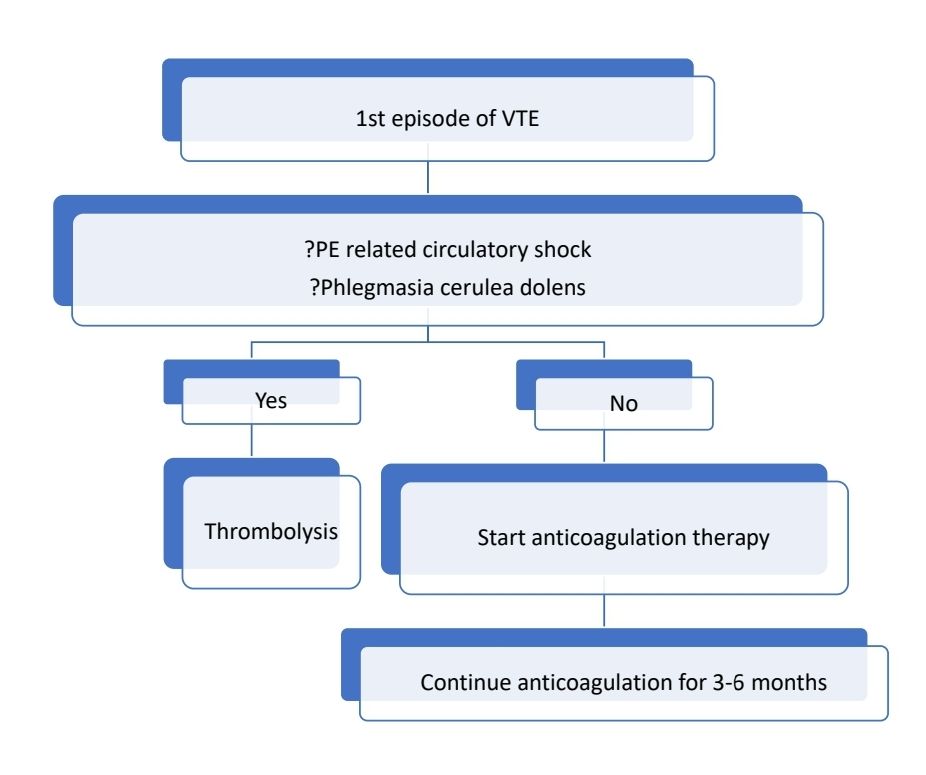

Treatment plan:

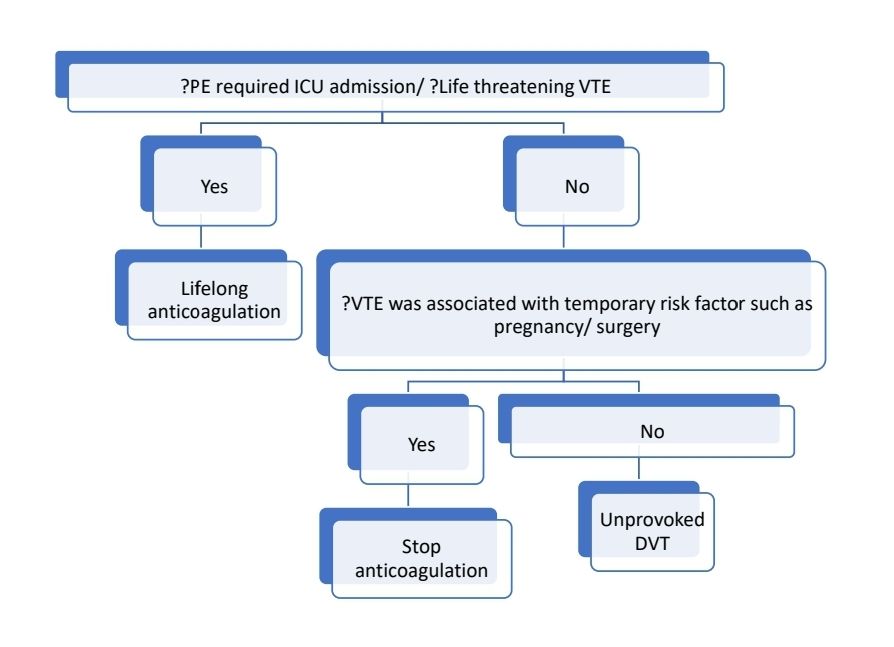

After 3-6 months

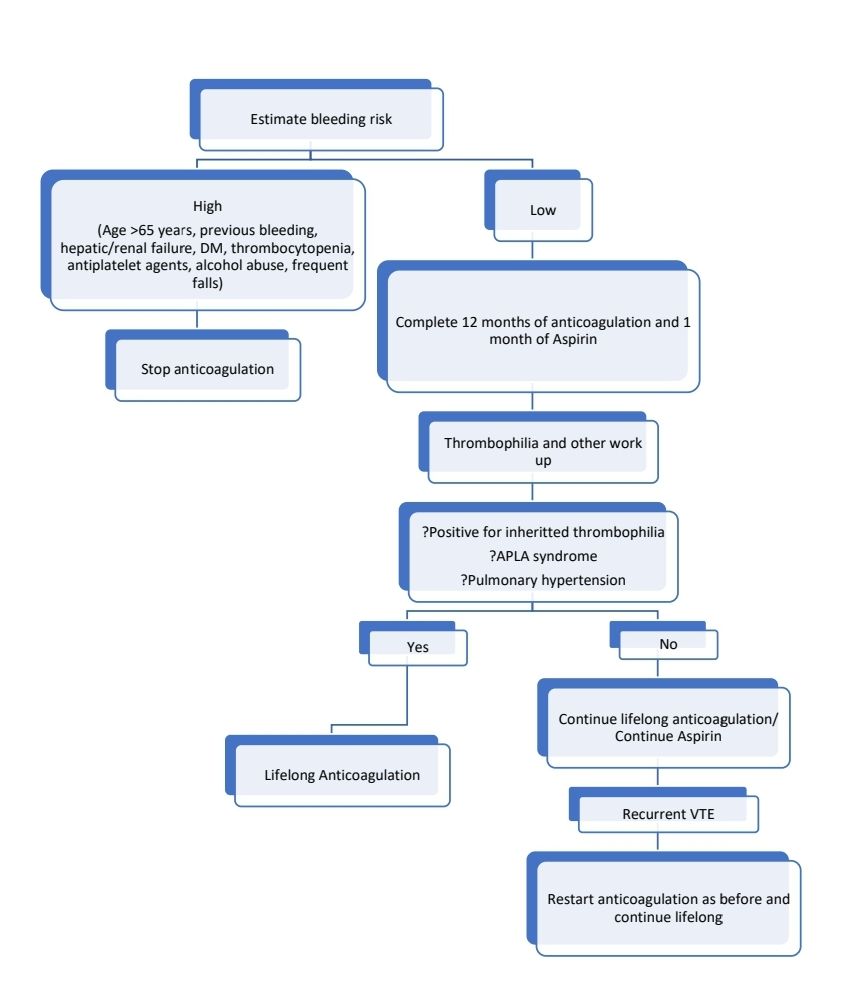

Unprovoked DVT (After 3-6 months of anticoagulation)

Treatment:

Acute DVT of leg involving proximal veins

- Options of initial therapy include:

- Parenteral anticoagulation (LMWH/Unfractionated heparin/Fondaparinux) along with Vitamin K antagonist (Warfarin- 0.05mg/Kg) on the same day.

- Parenteral anticoagulation for 5-10 days then startDabigatran.

- Rivaroxaban/ Apixabanstarted as single agent from day 1.

- If there is high clinical suspicion of DVT, parenteral anticoagulation may be started without waiting for diagnostic test reports.

- LMWH can be given in OD dosage, but dose should include same total dose of twice daily regimen.

- Ideally dose of Enoxaparin must be adjusted according to Anti-Xa levels.

- Catheter directed thrombolysis is advised in case of phlegmasiaceruleadolens, IVC thrombosis especially with suprarenal extension.

- Initial ambulation is advised. But it may be deferred if there is severe pain or edema. Compression therapy may be given to such patients.

- Use graduated compression stalking (40mm at ankle, 30mm at midcalf). Continue this for 2 years after an acute DVT.

- Initial treatment can be done at home, if circumstances are adequate (Well-maintained living conditions, strong support from family/friends, phone access and ability to quickly return to hospital if there is deterioration)

- Continue parenteral anticoagulation for at least 5 days, then check PT/INR. Continue parenteral anticoagulation until INR is ≥2 for at least 24 hours.

- There is no need for catheter directed thrombolysis, systemic thrombolysis, operative thrombectomy, IVC filter or venoactive medications such as Rutuside or defibrotide.

- Objectives of therapy include:

- Prevent death from pulmonary embolism

- Prevent morbidity from recurrent venous thrombosis/ PE

- Prevent or minimize post-thrombotic syndrome.

- Recommended target INR is 2.5 (Range- 2-3)

- VKA dose adjustments must be made on frequent basis. Computer assisted dosage adjustments are proven better than manual adjustments. If INR is consistently stable, it can be tested once in 12 weeks. For patients with stable therapeutic INRs, presenting with single subtherapeutic INR value, routine bridging with heparin is not required. If previous INR is stable, an out of range INR of <0.5 below or above therapeutic range, does not warrant change of dose. Instead repeat INR after 1-2 weeks.

- INR cards have to be maintained, indicating

- Indication for anticoagulation

- Target INR

- Duration of treatment

- VKA used

- Dose changes that are necessary

- Date of next INR check

- If any other drug is added, INR needs to be repeated after 3-5 days.

- Compression stockings are not necessary, but may help in decreasing post-thrombotic syndrome.

- Asymptomatic/ incidentally detected DVT also have to be treated.

- When stopping, stop abruptly, rather than tapering the dose.

- IVC filters

- They can be used if patient has acute proximal vein thrombosis and there is contraindication for anticoagulation. Even in such situations, conventional anticoagulation must be started once the risk of bleeding subsides.

- There is no evidence supporting their benefit in routine practice.

- Purpose is to prevent PE

- Site: Beneath renal veins

- Other relative indications

- Patients developing new VTE on therapeutic anticoagulation

- Patients undergoing pulmonary thromboembolectomy

- Extensive free floating ileofemoral thrombus

- Patients undergoing thrombolysis of an ilio-caval thrombus

- Complications:

- Immediate: Misplacement, pneumothorax, hematoma, air embolism, carotid artery puncture, AV fistula

- Early- Insertion site thrombosis, infection

- Late- Recurrent DVT, IVC thrombosis, post-thrombotic syndrome, IVC penetration, filter migration, filter tilting, entrapment of guide-wires

Acute DVT involving distal vein:

- If >5cm in length or >7mm in width, treat like DVT involving proximal vein.

- Do serial imaging every 2 weeks and start anticoagulation only if thrombus extends into proximal vein.

Superficial vein thrombosis:

- Superficial veins include peroneal, posterior tibial, saphenous, antecubital, basilic and cephalic veins.

- Risk factors as same as DVT, but additional risk factors include- varicose veins, intravenous catheters and septic thrombophlebitis associated with infections.

- Buerger disease (thromboangiitisobliterans) and Behcet’s disease are also associated with superficial vein thrombosis.

- Trousseau syndrome is migratory thrombophlebitis seen in patients with underlying cancer.

- If >5cm in length or if thrombus is near saphenofemoral junction- Prophylactic anticoagulation with LMWH/ Fondaparinus for 45 days.

- All others- Give only symptomatic treatment- analgesic/ anti-inflammatory agents and warm or cold compresses.

- Always do doppler to rule out DVT

- 3/4thare associated with varicose veins. If no varicose veins- look for underlying malignancy.

Acute pulmonary embolism with circulatory shock/ Massive PE (Systolic BP <90 mm of Hg):

- Thrombolysis with rtPA- 100mg- IV- over 2 hrs, then start heparin infusion

- Alternatively, streptokinase may be used

- If there is high risk of bleeding/ if systemic thrombolysis is contraindicated (Recent surgery/ invasive procedure, active bleeding, bleeding diathesis, recent stroke, active intracranial disease, pregnancy, uncontrolled hypertension, acute gastro-duodenal ulcer, hepatic failure, bacterial endocarditis)- catheter directed thrombolysis may be done. Dose: rtPA- 0.5-1mg/hr. In these cases, concurrent heparin infusion also should be started. After 6-18hrs, follow-up venogram/angiogram should be done to assess the extent of thrombus dissolution. Continue infusion till complete resolution of thrombus.

Stable acute PE

- Treatment is same as proximal DVT.

- Asymptomatic/ incidentally detected PE also have to be treated.

Directly acting anticoagulants:

- Advantages:

- No need of anticoagulant monitoring and dose titration.

- Fewer clinically relevant drug interactions.

- Rivaroxaban has faster onset of action, hence no need for LMWH cover during initial phase of treatment. Prior to staring Dabigatran initial therapy with LMWH for 5-10 days is necessary.

- Disadvantage:

- Specific antidote is not easily available, if there is bleeding.

Absolute contraindications for anticoagulation:

- Intracranial bleeding

- Recent brain, spine or spinal cord surgery

- Recent cerebrovascular accident

- Active GI bleeding

- Severe hypertension

- Severe renal/ hepatic failure

- Thrombocytopenia with platelet count <50,000/cmm

Monitoring:

- Persistent/ increasing edema (Need to rule out recurrent thrombosis)

- It is difficult as clinical manifestations are non-specific and doppler cannot pick up new thrombosis is previous thrombosis may not be completely recanalized.

- If leg pain is relieved by overnight rest and recurs with ambulation, it indicates post-thrombotic syndrome.

- Persistent swelling which is not relieved by rest suggests new DVT.

- D-Dimer based testing strategy is useful. If D-Dimer is positive, doppler is repeated. If it shows thrombus in segment of vein which was previously unaffected, it confirms the diagnosis of new thrombosis. If D-Dimer is negative, further testing need not be done.

- If there is recurrence/ progression of thrombus:

- Check for compliance and proper dosage

- If LMWH was used, increase the dose of LMWH by 25%

- If VKA was used, switch to LMWH and increase the target INR to 2.5- 3.5

- Alternatively, consider adding another anticoagulant or switch to another anticoagulant

- Look for APLA syndrome (as it can spuriously increase INR values), underlying malignancy and anatomic cause for thrombosis

- For post thrombotic syndrome:

- Use graduated compression stalking (40mm at ankle, 30mm at midcalf)

Prophylaxis:

- LMWH- OD dosage or UFH- 5000 units BD, DOACs are approved in Total Knee/Hip replacements.

- In patients who are bleeding or are at high risk of bleeding- Use Graduated compression stockings or intermittent pneumatic compression devices. They are better than no prophylaxis. Once bleeding risk subsides, switch to pharmacological prophylaxis.

- All medical patients, older than 40 years, who are expected to have at least 3 days of admission and have any one of following risk factors, should receive DVT prophylaxis

- Acute infectious disease

- Congestive cardiac failure

- Stroke

- Acute pulmonary disease

- Acute rheumatic disease

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Sickle cell crisis

- Critical illness

- In surgical patients Caprini score is used to identify those who need LMWH prophylaxis. But it is very complicated to follow. In general, following patients must receive DVT prophylaxis 12 hrs post operatively for 7-14 days, till they are completely mobilized.

- Surgery lasting for >45 min or general anaesthesia greater than 30min

- Elective arthroplasty

- Major trauma

- Hip/ pelvic bone/ leg bone fracture

- Patient is likely to be immobile following surgery (Stroke/ spinal cord injury within past 1 month)

- Previous history of VTE/ Underlying thrombophilia including APLA syndrome/ Pregnant/ Immediate postpartum

- No prophylaxis is required for chronically immobilized patients residing at home or at a nursing home.

- Prophylaxis for travel related VTE

- Risk is 1.7% with travel for >8 hrs in individuals with low risk

- Risk of fatal PE- 0.5 per million for flights over 3 hrs

- Compression stockings are effective, but are not recommended for global use.

- Routine thromboprophylaxis with heparin/ LMWH is not recommended.

- It should be given to following high risk individuals

- Recent trauma or surgery

- Previous VTE

- Presence of varicose veins

- Active cancer

- Hormone therapy

- Severe obesity

- Maintaining mobility is a reasonable precaution for all travellers on journeys over 3 hrs.

- There is no evidence that good hydration helps in preventing VTE.

- Methods of providing DVT prophylaxis

- Compression stockings/ pneumatic compression devices

- Heparin-SC-TID or LMWH- SC- OD

Special Situations:

- VTE and pregnancy

- Risk of VTE is 5 times higher in pregnant, as pregnancy is a prothrombotic state.

- Causes for increased risk include

- Venous stasis by enlarged uterus

- Hormonally induced venous dilation

- Increased procoagulants in 3rd trimester- Factor 8, factor 9, fibrinogen, vWF etc

- Decreased protein S levels due to increased levels of C4B binding protein

- Decreased fibrinolytic activity

- Venous atonia caused by hormonal factors such as estrogen

- Incidence of VTE- 1 in 1000 pregnancies

- VTE accounts for 12% fatalities in pregnant

- Risk factors include

- Age- More than 35 years

- Obesity (BMI >29)

- Caesarean delivery

- Prolonged immobilization

- Thrombophilia

- Family history of VTE

- Multiparity

- Ovarian hyperstimulation

- Past history of VTE

- If any of these risk factors are present, consider giving prophylactic LMWH.

- 90% of VTE in pregnancy are DVT of left leg, as enlarged uterus compresses left iliac vein

- Compression USG is the investigation of choice. If PE is suspected do lung ventilation perfusion scanning or MR venography (Avoid Gadolinium). No need to evaluate for PE if mild symptoms are present and DVT is proved by doppler, as treatment of DVT and mild PE remain same.

- If required CT Angiogram can be done with appropriate abdominal shielding.

- D-Dimer is a poor test for diagnosis of VTE during pregnancy

- Warfarin and other non-heparin anticoagulants are teratogenic and can cause fetal haemorrhage, hence should not be used. DOACs cross placenta and may case hemorhhage in fetus.

- Use Unfractionated heparin (250units/Kg-BD) or LMWH (Preferred) during the entire course of pregnancy as they do not cross placenta.

- Fondaparinux is probably safe, and can be used if there is development of heparin induced thrombocytopenia.

- Thrombolysis or thrombectomy should be done if there is PE causing hemodynamic instability. This has 8-15% of risk of major bleeding. In post partum period risk of major bleeding is 58%.

- Stop 24 hrs prior to induction of labour or LSCS.

- Avoid epidural anaesthesia

- Restart once complete haemostasis is achieved.

- After delivery, VKA may be added. In that case LMWH is discontinued once INR is in therapeutic range.

- Anticoagulation should be continued for 6 weeks post-partum (for total minimal duration of 3 months). If monitoring INR is difficult, remaining on LMWH is an option. DOACs are secreted in breast milk, hence should be avoided.

- For women requiring long term anticoagulation, who are attempting pregnancy and are candidates for LMWH substitution, ACCP suggests, performing frequent pregnancy tests and substituting LMWH for VKAs when pregnancy is achieved rather than switching to LMWH while attempting pregnancy.

- During breast feeding Warfarin can be continued, but adequate dose of vitamin K should be given to child.

- Avoid routine thromboprophylaxis for women undergoing assisted reproduction. Give LMWH for 3 months only if they develop severe ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome.

- Prophylactic LMWH must be given if there is previous history of unprovoked/ provoked VTE, APLA syndrome or patient has underlying thrombophilia mutations especially Factor V Leiden and prothrombin gene mutation. Prophylaxis must be continued during postpartum period for duration of 6 weeks. Although risk of VTE is less with some thrombophilias, chances of pre-eclampsia can be decreased with use of LMWH. Doses of anticoagulants for prophylaxis

- Unfractionated heparin

- 1st trimester- 5,000 units- BD

- 2nd trimester- 7,500-10,000 units- BD

- 3rd trimester- 10,000 units- BD

- Enoxaparin- 0.6mg/Kg/day- OD

- Unfractionated heparin

- Patients with pregnancy related VTE must avoid exposure to exogenous estrogens including estrogen containing OCPs and hormone replacement therapy. Lose dose vaginal estrogens may be used if patient has significantly symptomatic post menaupausal vaginal atrophy.

- Thrombosis in neonates and children

- Seen in 1:1,00,000 neonates

- Most commonly it is because of indwelling catheters

- Thrombolytic therapy is needed if thrombosis is life or limb threatening. rTPA: 0.1 to 0.5mg/kg/hr for up to 6hrs. Give FFP 10ml/kg prior to thrombolysis. Avoid if there is risk of bleeding/ active bleeding.

- Treatment is same as DVT in adults, but treatment should be done in combination with paediatrician.

- Use of warfarin is not recommended, as liquid preparation is not available and monitoring is difficult.

- Enoxaparin- 1mg/kg SC- every 12 hrly

- Cancer associated VTE

- Common with cancers involving pancreas, stomach, brain, kidney, lung and ovary.

- Potential risk factors include

- Congenital thrombophilia

- Use of central catheters- Risk is more with PICC line compared to tunnelled catheter.

- Obstruction by tumor

- Hypercoagulable state induced by tumor

- Major surgery for excision of tumor

- Therapeutic agents such as steroids and L asparaginase

- Use of combined OC pills for suppression of menstruation

- Preventive measures include

- Good hydration

- Early mobilization

- Removal of central venous catheters when not required

- Avoid use of combined OC pills. Use progestogens such as norethisterone, medroxyprogesterone acetate etc.

- L asparaginase decreases Antithrombin, Protein C and S levels. Hence when using L asparaginase, for high-risk patients, FFP can be administered as replacement therapy. But this also repletesasparagine pool, hence it may decrease leukaemia remission rate.

- Prophylaxis has to be given in presence of precipitating factors which include:

- Major surgery

- Chemotherapy particularly cisplatin

- Hormonal therapy

- Anti-angiogenic agents- Bevacizumab, sunitinib, sorafinib

- Immunomodulatory drugs- thalidomide, lenalidomide

- Erythropoiesis stimulating agents

- Parenteral anticoagulation (LMWH) is preferred for treatment and also for prophylaxis. (Full therapeutic dose should be given for 4 weeks and 75% of therapeutic dose thereafter)

- For patients who have developed VTE, anticoagulation should be continued at least for 6 months and then till complete resolution of cancer.

- Catheter related thrombosis:

- Catheter need not be removed if it is functional and there is ongoing need for catheter.

- Continue anticoagulation till catheter is in situ and then continue for 3 months after removal of catheter.

- Perioperative anticoagulation for patients on warfarin/ DOACs

- Warfarin need not be stopped for procedures with minor bleeding risks such as joint injections, cataract surgery, pacemaker insertion, endoscopy and mucosal biopsy, minor dental and dermatological procedures.

- Stop VKA 5 days prior to surgery and at the same time start bridging with LMWH.

- INR is measured 1 day prior to surgery, and if INR is >1.5, Vitamin K should be given.

- LMWH should be stopped 24 hrs prior to surgery and in the last dose 50% of dose should be given.

- INR must be checked on the day of surgery.

- LMWH (therapeutic dose) and Warfarin (at previous maintenance dose), can be resumed, the evening of surgery or the next day, if there is adequate haemostasis.

- Regarding DOACs- consideration should be given to half-life of the drug and renal function. Discontinuation of 48hrs is sufficient for most of the patients. They must be restarted only after complete haemostasis has been secured (usually 48- 72hrs post procedure)

- Tranexamic acid can be used to reduce bleeding in patients who have a residual anticoagulant effect.

- Avoid drugs that affect haemostasis perioperatively.

- Stop Rivaroxaban, Apixaban, and Endoxaban 2 days prior to surgery. Stop Dabigatran 5 days prior to surgery.

- Emergency surgery in patients on warfarin

- If surgery can wait for 6-8hrs, then give Vitamin K 5mg to restore coagulation factors.

- If waiting is not possible, transfuse FFP/ Prothrombin complex concentrate.

- Post operative management is same as above.

- Combination and warfarin with antiplatelet agent

- Combination increases bleeding risk significantly

- If antiplatelet agents are being given as primary prophylaxis of coronary artery disease, stop antiplatelet agents. Combination therapy does not have superior antithrombotic therapy.

- If antiplatelet agent was started for acute coronary syndrome, it has to be continued.

- If patient on warfarrin develops indication for antiplatelet agent, assess the need for continuing warfarin. If not required discontinue warfarin. If continuation is required, limit dual therapy for minimum duration of time. If patient needs coronary artery stent, bare stent is better than drug eluting stent.

- VTE with thrombocytopenia

- Therapeutic anticoagulation can be continued, if platelet count is >50,000/cmm

- If thrombosis is recent onset (<1month)/ was life threatening, then platelets must be transfused with target platelet count of 50,000/cmm and therapeutic anticoagulation must be continued.

- In other cases, if platelet count is between 25,000/cmm to 50,000/cmm, anticoagulation dose must be decreased to 50%. If platelet count is <25,000/cmm, anticoagulation must be temporarily interrupted.

Related Disorders:

- Mesenteric/ Portal/ Splanchnic vein thrombosis:

- Presents with splenomegaly and esophageal- gastric varices.

- Occur usually secondary to local causes such as pancreatitis, cirrhosis, tumor or infection.

- Other causes include- MPN, PNH and thrombophilia

- Anticoagulation must be given only if patient is symptomatic.

- Anticoagulation must be continued for 3-6 months. Long term anticoagulation is avoided if there is high risk of bleeding.

- Surgery is required if bowels have become necrotic.

- Anticoagulation is not required if it is incidentally detected.

- Budd Chiari Syndrome (Hepatic vein occlusion)

- Presents with hepatomegaly and right upper quadrant pain.

- Often associated with MPN (especially PV), thrombophilia or malignancy.

- Consider thrombolysis in acute setting

- Decision to anticoagulate should be based on extent of liver damage and subsequent risk of bleeding.

- TIPSS is preferred mode of treatment.

- If this fails liver transplantation is the next choice of treatment.

- Ovarian vein thrombosis:

- Seen in 1 in 1000 pregnancies

- Presents within 4 weeks of delivery

- May extend to renal veins

- Treated with conventional anticoagulation- for 3-6 months

- Penile vein thrombosis (Mondor disease)

- Benign, painful, cord like thrombus in dorsal penile vein

- Treat with analgesics.

- Anticoagulation is not required.

- Superior vena cava thrombosis

- Etiology: Malignancy (60% cases), indwelling catheters, infections, mediastinal fibrosis

- Clinical features: Swelling of face/ neck, upper limb swelling, dyspnea, cough, dilated chest vein collaterals

- Investigations: CT scan chest, Contrast venography if endovascular interventions are planned.

- Anticoagulation must be started immediately to prevent PE. In case of severe symptoms with benign SVC thrombosis- Endovascualr surgery with angioplasty and stenting is the treatment of choice.

- If secondary to malignancy, radiotherapy should be given.

- Anticoagulation is needed on long term basis.

- Inferior vena cava thrombosis

- Presentation and management are same as DVT

- Jugular vein thrombosis

- Often seen in association with local sepsis, inflammation or trauma.

- Needs anticoagulation for 3 months

- Lemierre syndrome: Oropharyngeal infection with internal jugular vein thrombosis. It is secondary to infections due to anerobes such as Fusobacteriumnecrophorum.

- Retinal vein thrombosis

- Incidence in >40 years- 1.6/1000 people

- Presents with acute painless loss of vision

- Risk factors- Hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, diabetes, glaucoma

- Later leads to macular edema and neovascularization

- Treatment

- Laser photocoagulation

- Local injection of steroids for macular edema

- Antiangiogenicagents such as bevacuzimab

- Role of anticoagulation in preventing recurrence is not known. In fact this can increase the risk of hemorrhage.

- Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis

- 75% cases are seen in women

- Account for 1% of all strokes

- Annual incidence: 1-2/1,00,000 population

- Can lead to venous infarction and cerebral edema

- Etiology: Infections in head and neck, systemic inflammatory/ autoimmune diseases, malignancies, leukemias, MPN, head injury, dehydration, pregnancy and puerperium, OC pills/ Asparaginase/ steroids, Prothrombotic states (Genetic/ acquired).

- Pathogenesis:

- Thrombosis leads to obstruction to venous drainage from brain tissue. This results in cerebral parenchymal damage and increased cerebral volume (due to both cytotoxic and vasogenic edema).

- Occlusion of venous drainage also decreases CSF absorption, resulting in increased intracranial pressure.

- Present with head ache (due to intracranial hypertension), focal neurological deficits, seizures or encepalopathy

- MR venography is diagnostic. Changes include:

- Absence of flow in venous sinus (Other condition mimicking these changes include: sinus atresia, sinus hypoplasia, asymmetric sinus drainage, normal sinus filling defects associated with arachnoid granulomas)

- Focal areas of edema/ venous infarction

- Hemorrhagic venous infarction

- Diffuse brain edema

- Rarely isolated subarachnoid hemorrhage

- CT and Brain MRI are often unrevealing. But may show following changes:

- The cord sign, dense triangle sign and empty delta sign.

- Cerebral infarction that crosses typical arterial boundaries

- Hemorrhagic infartcion

- Lobar intracerebral hemorrhage

- Elevated D-Dimer supports diagnosis of CVST but normal values do not exclude CVST.

- Endovascular thrombolysis/ mechanical thrombectomy may be considered only in selected patients, where there is extensive CVST that may be immediately fatal/ there is progressive neurological worsening in spite of LMWH.

- Measures to decrease intracranial pressure: head end elevation, mild sedation, Mannitol, and hyperventilation with target PaCO2 of 30-35 mmHg. Dexamethasone is useful if there is underlying autoimmune disease (Lupus/ Behcets/ vasculitis).

- Antiepileptics for seizure treatment/ prevention (Preferably Levetiracetam)

- Antibiotics if there suspicion of meningitis/ otitis/ mastoiditis.

- Surgical decompression should be done is there are signs of impending herniation.

- Start parenteral anticoagulation (preferably LMWH) immediately if there is no contraindication. Presence of haemorrhagic infarct/ intracerbral hemorrhage/ isolated subarachnoid hemorrhage is not a contraindications for anticoagulation.

- Both Vitamin K antagonists (Target INR- 2-3) and direct oral anticoagulants may be used after acute phase.

- Continue anticoagulation for 6 months to 1 year. 2-3 weeks after discontinuing anticoagulation, do thrombophilia work up incluing APLA and PNH. If there is further risk of thrombosis, give long term anticoagulation.

- 80% of surviving patients recover completely. Recanalization occurs in first 4 months.

- Renal vein thrombosis

- Presents with triad of acute flank pain, hematuria and sudden deterioration of renal function.

- In addition to routine evaluation, also evaluate for nephrotic syndrome.

- Treatment: Same as DVT

- Upper extremity DVT

- Brachial, axillary, subclavian and brachiocephalic veins are considered as deep veins.

- Causes: Indwelling catheters, local trauma, upper limb immobilization in plaster cast, thoracic outlet/ Paget Shroetter syndrome (Subclavianvein is compressed by cervical rib, hypertrophied anterior scelene muscle or costo-clavicular ligament)

- 1/3rd patients have PE

- Treatment is same as DVT.

- May Thurner syndrome

- Chronic compression of left common iliac vein between the overlying right common iliac artery and the fifth lumbar vertebral body posteriorly

- If these patients develop DVT, after routine treatment, consider correction of stenosis by balloon angioplasty and stenting. After stenting, anticoagulation should be continued for 3 months. Then assessment must be made to identify need for long term anticoagulation.

Recent advances:

Incidence and impact of anticoagulation-associated abnormal menstrual bleeding in women after venous thromboembolism

The TEAM-VTE study was an international multicenter prospective cohort study in women aged 18 to 50 years diagnosed with acute venous thromboembolism. Menstrual blood loss was measured by pictorial blood loss assessment charts at baseline for the last menstrual cycle before VTE diagnosis and prospectively for each cycle during 3 to 6 months of follow-up. AUB occurred in 60% of women without AUB before VTE diagnosis.In conclusion, 2 of every 3 women who start anticoagulation for acute VTE experience AUB, with a considerable negative impact on QoL.

https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2022017101

Hypoxia and low temperature upregulate transferrin to induce hypercoagulability at high altitude

Transferrin is known to potentiate blood coagulation. Present study examined the activity and concentration of plasma coagulation factors and transferrin in plasma collected from long-term human residents and short-stay mice exposed to varying altitudes. It was found that the activities of thrombin and factor XIIa (FXIIa) along with the concentrations of transferrin were significantly increased.

https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2022016410

Low-molecular-weight heparin versus standard pregnancy care for women with recurrent miscarriage and inherited thrombophilia

Studies have shown an association between recurrent miscarriage and inherited thrombophilia. The ALIFE 2 trial included women (18-42 years) who had two or more pregnancy losses and confirmed inherited thrombophilia. They were randomly assigned (1:1) to use subcutaneous LMWH once daily (enoxaparin 40 mg, dalteparin 5,000 IU, tinzaparin 4,500 IU or nadroparin 3,800 IU) versus standard pregnancy surveillance once they had a positive urine pregnancy test. Observed live birth rates were 116/162 (71.6%) in the LMWH group and 112/158 (70.9%) in the standard surveillance group. Compared with standard surveillance, the use of LMWH did not result in higher live birth rates in women who had two or more pregnancy losses and confirmed inherited thrombophilia.

https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2022-171707

Recurrence after stopping anticoagulants in women with combined oral contraceptive-associated venous thromboembolism

In the present analysis 19 studies were identified including 1537 women [5828 person-years (PY)] with COC-associated VTE and 1974 women (7798 PY) with unprovoked VTE. The incidence rate of VTE recurrence was 1.22/100 PY in women with COC-associated VTE, 3.89/100 PY in women with unprovoked VTE and the unadjusted incidence rate ratio was 0.34. The recurrence risk in women after COC-associated VTE is low and lower than after an unprovoked VTE.

https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.18331

Impact of Paxlovid on international normalized ratio among patients on chronic warfarin therapy

Paxlovid (nirmatrelvir-ritonavir) is used for the treatment of patients with mild to moderate COVID-19. Among high-income countries, 1% to 2% of the population is prescribed long-term anticoagulants. Ritonavir is a potent inhibitor and inducer of key drug-metabolizing enzymes. Thus, coadministration of ritonavir with warfarin can have variable effects on the efficacy of warfarin. Study suggested that, there is no need for empiric holding doses of warfarin when taking Paxlovid and recommended close monitoring of INR, especially in the immediate post- Paxlovid period.

https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2022017433

Apixaban as secondary prophylaxis of a primary venous thromboembolism in children and adolescents

The standard treatments, warfarin and low molecular weight heparin (LMWH), have limitations in the pediatric population. This phase II pilot study was conducted, involving 26 patients, and apixaban was administered orally according to a specific dosage regimen. Imaging assessments showed positive responses with complete or partial thrombus resolution. No new VTE events occurred during the study, and no significant bleeding or adverse events were reported. The preliminary results suggest that apixaban is feasible, safe, and effective as secondary prophylaxis in this population.

https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.18804

Inflammatory biomarkers and venous thromboembolism

The study compiled data from 25 articles and found that elevated levels of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) and C-reactive protein (CRP) greater than 3ug/ml are potential risk factors for future VTE occurrence. Additionally, increased levels of certain markers, including monocyte, hs-CRP, CRP, and IL-6, may indicate a history of VTE. During the acute phase of VTE, markers like white blood cells, neutrophils, monocytes, hs-CRP, IL-6, platelet-lymphocyte ratio, and neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio showed increased levels.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12959-023-00526-y

A signature of platelet reactivity in CBC scattergrams reveals genetic predictors of thrombotic disease risk

A study involving 29,806 blood donors utilized a model trained to predict platelet reactivity (PR) from complete blood count scattergrams, identifying 21 associations involving 20 genes, including six previously identified. The effect size estimates were correlated with those from other PR studies, and a genetic score of PR was associated with myocardial infarction and pulmonary embolism incidence rates. Mendelian randomization analyses suggested a causal association between PR and the risks of coronary artery disease, stroke, and venous thromboembolism. The study demonstrates a blueprint for using phenotype imputation to investigate determinants of challenging-to-measure hematological traits.

https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2023021100

Factors associated with venous thromboembolic disease due to failed thromboprophylaxis

In a study evaluating factors associated with failed thromboprophylaxis (FT) in hospitalized patients, 204 cases and 408 controls were analyzed. Factors independently associated with FT included higher BMI (odds ratio [OR]: 1.04; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.00-1.09), active cancer (OR: 1.63; 95% CI 1.03–2.57), leukocytosis (OR: 1.64; 95% CI 1.05–2.57), and the requirement for intensive care (OR: 3.67; 95% CI 2.31–5.83). The study suggests that adjusting thromboprophylaxis in patients with these factors may be beneficial and highlights the importance of considering these risk factors in thromboprophylaxis strategies.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12959-023-00566-4

Treatment and prophylaxis of VTE patients with renal insufficiency

This study conducted a meta-analysis of twenty-five randomized controlled trials (RCTs) involving 9,680 participants with renal insufficiency (RI) who had venous thromboembolism (VTE). Results showed that in the acute phase, novel oral anticoagulants (NOACs) increased the risk of bleeding compared to low molecular weight heparin (LMWH). For VTE prophylaxis, NOACs were associated with a higher risk of bleeding compared to placebo. Both NOACs and vitamin K antagonists (VKA) increased bleeding risk in RI patients compared to non-RI patients during the acute phase. Additionally, NOACs may increase the incidence of VTE in RI patients. The study suggests that LMWH is the most effective and safe option for VTE treatment or prophylaxis in RI patients.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12959-023-00576-2

Implementation of early prophylaxis for deep-vein thrombosis in intracerebralhemorrhage patients

This study assessed the implementation of early deep-vein thrombosis (DVT) prophylaxis in 49,950 patients with intracerebralhemorrhage (ICH) in China. The rate of early DVT prophylaxis was found to be suboptimal, with only 49.9% of patients receiving it within 48 hours of admission. Factors associated with increased likelihood of early DVT prophylaxis included early rehabilitation, admission to specialized units, certain medical histories, and higher Glasgow Coma Scale scores. Conversely, being male, hospitalized in tertiary hospitals, and having a history of previous intracranial hemorrhage were associated with lower likelihood of early DVT prophylaxis.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12959-024-00592-w

An Initiative of

Veenadhare Edutech Private Limited

1299, 2nd Floor, Shanta Nivas,

Beside Hotel Swan Inn, Off J.M.Road, Shivajinagar

Pune - 411005

Maharashtra – India

howitreat.in

CIN: U85190PN2022PTC210569

Email: admin@howitreat.in

Disclaimer: Information provided on this website is only for medical education purposes and not intended as medical advice. Although authors have made every effort to provide up-to-date information, the recommendations should not be considered standard of care. Responsibility for patient care resides with the doctors on the basis of their professional license, experience, and knowledge of the individual patient. For full prescribing information, including indications, contraindications, warnings, precautions, and adverse effects, please refer to the approved product label. Neither the authors nor publisher shall be liable or responsible for any loss or adverse effects allegedly arising from any information or suggestion on this website. This website is written for use of healthcare professionals only; hence person other than healthcare workers is advised to refrain from reading the content of this website.